AMENITIES

Seth Kantner enjoys the amenities in his sod home near Ambler, Alaska. Image by Dorene Cameron Schiro

COMMUNICATING IN THE BUSH

One way to cope with the loneliness of a remote homesite is to find other ways to communicate with people rather than face-to-face interactions. The two methods I mainly used were mail and radio. These days it’s also possible to stay in touch via email and the Internet.

I keep a mailbox inside of a barrel standing on the lakeshore beside my homesite. When I want to send mail, I set the mailbox on top of the barrel so that George Hobson, a bush pilot, can see it when he flies over in his float plane. He picks it up when it’s convenient for him. He lives in Fairbanks and has a place on a nearby lake, too.

He puts whatever he’s brought to me into the box and takes the outgoing mail. If he doesn’t have time to come up for a visit, he circles the house to let me know he’s been by.

When I hear his plane I come outside, especially if he makes an extra buzz around. Sometimes he does air drops of supplies. One time I ran out of medicine and he brought me a refill. As soon as he saw me standing outside, he circled around, flew over, and threw it out his window. It had a long streamer on it to show me where it landed.

Ham Radio

For a while I had a small amateur radio and got a license. [Oliver trained as a radioman during World War II.] Eventually I set that radio up over at my neighbors’ place and ended up giving it to the couple.

The radio allowed the woman to be somewhat in contact with the outside world when her husband was away working from January through April. She could hear what other people were doing as they communicated back and forth on the channels. She knew that if she ever needed to, she could cut in and make contact with them.

Once when this happened, there was a man who right away wanted to know if she had a license, what her call sign was, and so forth. He didn’t seem to understand our situation out in the bush. With his fancy equipment and his expensive office, I don’t think he’d ever been out of town. I spent some time talking to him, explaining what it was like to be out in the bush in a remote area, and how this radio was a vital thing out here for connecting people and making is feel like we had a lifeline.

CB Radio

I also gave or loaned my same neighbor one of my CB radios. [Citizen Band radios allowed for shorter-distance personal communications.] She used it to talk with me and our other neighbors, Duane and Rena Ose.

I use a short, half-wave sloper for an antennae on my CB radio. The end of it is quite high, and the bottom is fastened to the roof of my house. It slopes at maybe 30 degrees from the vertical. Since most of the people I talk to are north or northeast of me, I aim the antenna to transmit mainly in that direction.

Usually everybody in the area turns on their CB at about 8:00 p.m., when we’re all inside. We can hear everybody talking who’s within range.

I don’t talk much, but some long-winded people can talk for an hour. Sometimes I have to break in on them so that I can check in and go to bed. When they run out of wind and there’s a pause, I’ll jump in and make contact with Rena, just so she’ll know I’m still alive and won’t worry about me.

I’m mostly on channel five. If I want to talk with somebody and that channel is busy, I’ll break in, give them a call, and tell them to go to another channel, like seven or eight.

Ordinarily I run the radio off small batteries. I try to cycle those small batteries between 10 volts and 11 volts. That seems to work for the CB. I don’t drain the batteries way down. I figure they’re about dead when they’re at 10 volts.

Only occasionally do I have to switch over to big batteries.

There have been a few times when the CB was useful. One time Rena was worried about Duane when he’d been out for a long time. She called me and told me she was thinking of going out to look for him. I told her to wait. I didn’t want her going off by herself. My other neighbor went up to the Oses’ with his dog team, and by that time, Duane had made his way home.

Another important radio resource is the local AM radio stations. The stations in Nenana and Fairbanks broadcast messages for people in the bush two or three times daily, at specified times. It’s an excellent and fun way to stay in touch. People call in to the radio station and record their message, which is then played at message time.

For an extra boost of security, I also had an emergency locator transmitter. [An emergency locator transmitter (ELT) is a personal tracking beacon that sends out a distress signal when activated. Satellites pick up the signal, allowing search-and-rescue personnel to determine the location of the device and send help.]

* * *

The following is an excerpt from a tribute to Oliver that Duane Ose wrote.

It is a long ways from Oliver’s place to mine—a one day’s journey on foot through the jungles of Alaska. He came up to our place several times, and would stay a day or two before he and whatever dog he had at the time would trudge on back, the dog toting the gear in the rear. One time our dog had pups and Oliver spent time picking the right one for his dog-to-be.

Then at some time Rena and I got fancy and got a cell phone. I had to build a tower for the antenna to get a signal from the main tower some 80 miles away. Those were the days of analog, when signals reached far. Now 30 miles is the limited range for a digital cell phone, so we had to get a satellite dish and Internet to keep in touch with the world.

At that time a working cell phone cost us $145.00 per month on average, though we used it only two or three times on a weekend. During those times, we worked out a strange system of relaying calls from Dorene to her dad Oliver at the lake via cell-phone-to-CB radio relay.

This is how we did it: At a set time, Oliver would be standing by at his end, and Rena at the dugout on her CB. I would be up on top of our high hill and tower, with the cell phone and a CB, too. I would call Rena to confirm that Oliver was ready. Then I would call Dorene, if she had not already been on the line with me.

Dorene and I would talk first, and again just after Oliver’s talk.

“Okay. Ready? Hello, Dad! Hello, Dorene.”

Mind you, during this time I was listening in. I had to, in order to know who was talking and when I had to hold the CB earpiece to the cell, or the speaker to the cell. It got downright interesting, keeping track of the positioning of the speaker to mic, or vice versa.

After the phone-to-CB was over, Rena would be talking with Oliver on the CB, and Dorene always wanted to rubberneck to hear what they were saying.

Oliver and Dorene both so enjoyed those calls, and Rena and I were happy to be in the middle of the calling. So you should know that Dorene was a long-distance rubbernecker of the strangest calling service ever on this Earth.

I sure miss the Analog system, but if we still had it we would not now have the Internet and the world at our fingertips. These days, Oliver could be conversing with Dorene through Skype.

LIGHTING

When the days are short in the wintertime, you can do a lot of work by moonlight because of the snow. Even if the moon is just a little sliver, its light reflects off the snow enough for doing ordinary outdoor chores, so long as you’re familiar with your environment.

I use my daylight hours for indoor chores, and when the light dims inside the house, I go outside. I could do some pretty hefty work by moonlight, such as getting poles and felling small trees. With enough moonlight, a fellow could work out there all night if he wanted. [A phenomenon called airglow or nightglow produces diffuse light in the upper atmosphere. It is caused by atoms and ions that have been excited by sunlight and later release the energy as visible light. Snow on the ground magnifies this effect.]

I also do quite a bit of outside work by lamplight—cutting wood, unloading sleds, or even loading them when I want to get an early start before daylight.

I stick my peavey into the ground or snow in the work area and hang a Dietz kerosene lantern in a groove cut in the end of the peavey’s handle. A Dietz lantern has a lever that I lift to raise the globe when I light the wick. When I let the lever back down, the glass keeps the wind from blowing out the flame.

Dietz Kerosene Lantern. (Image credit 51)

I also use kerosene lamps indoors. The lamps with a round wick give more light and heat than those with a flat wick. Some, like Aladdin lamps, also have mantles [a device for generating bright white light when suspended over heat and flame]. Any kind of mantle lamp gives off more light and is more efficient than one that just has a flame burning off a wick.

Aladdin lamps can be difficult to use. The size of the flame varies with the heat in the room. If you start using it in a cold house and then the house warms, the flame gets bigger. The lamp makes a unique sound when it starts taking off like that. If you don’t notice it, you get a smoked-up chimney and there may be flames coming out the top. It can be dangerous. People need to be careful and pay attention while using Aladdin lamps.

Flat wicks require a lot of trimming. If you don’t trim them every time you use them, they get carboned up, which can send up little spikes of flame and smoke. Some folks consider flat wick lamps more economical, and it’s true that mantle lamps with round wicks use kerosene faster, but you’re also getting a lot more light from them. In either case, it pays to keep your chimney clean!

Whenever I use a kerosene lamp indoors, I set it on a shelf inside the house near an open stovepipe to allow the fumes to vent. Some warm air from inside the house is always going out through the stovepipe, unless it is closed it off, so the system acts like a chimney, drawing the emissions from the lamp outdoors. This system works quite well for reducing the odor and exhaust fumes of a kerosene lamp.

I always allow for air circulation in the house when using the lamp. When I turn off the lamp, I let the fumes come off the wick until I don’t smell it much, and only then do I close my stovepipe.

In Ambler, I bought kerosene by the barrel. We were using Aladdin lamps at that time. I normally bought a 55-gallon drum of kerosene every three years.

Living by the lake, I often get my kerosene in 5-gallon cans, but a few years ago there was a commercial outfit that brought a bunch of equipment through to build a new plane runway. They had a Caterpillar dozer fall through the ice, and it was down in the water. They had to camp near the lake for a while as they flew in equipment to get that Cat out and running again.

While that was going on, I did some favors for the fellow who owned that outfit. He used my ham radio quite often. When he was getting ready to bring a big heavy scraper out, he offered to bring me a barrel of kerosene, so I bought the kerosene and he hauled it out there.

My kerosene consumption really dropped after I got solar panels and batteries and especially after I started using LEDs [lighting products using Light Emitting Diodes]. After that, I only used maybe a couple of gallons of kerosene. Before, I was probably using four or five gallons a year. I didn’t ordinarily try to light the whole house—just enough to see my way around. If I had work that needed more focused light, I took it closer to the lamp.

I use a Coleman double-mantle gasoline lantern when I am working inside my Quonset workshop at the lake.

Coleman two-mantle gasoline lantern. (Image credit 52)

I also sometimes use carbide lamps. A favorite is a headlamp mounted on a hat.

A carbide lamp has a lever on it that allows you to adjust the amount of water that drips onto the carbide. You regulate that water drip to control the size of your flame. Once the water has been used up by the carbide, the carbide won’t off-gas any more. Whatever is left, you can use again.

To turn off the light, you just shut off the water. The light will go out, but it’s not like turning off an electric lamp. When you shut it off, the flames die down gradually, and quite often there will be just a little tiny bit of a flame that will last for quite a while.

If I’m going to be using the carbide lamp for a few minutes, I turn it down to hardly any flame, and it keeps burning. When I open up the water supply and let it run again, it’s ready to go.

The carbide in my headlamp lasts quite a while. For enough light to walk along a trail, I can get three hours out of it.

Some lamps have bigger water reservoirs than others. My tank only holds about 1/4 cup of water.

Carbide lamps were once used for coal mining, and also tunnel work or underground work, but they presented a certain amount of hazard, because if explosive gases built up underground in confined spaces, the lamp could ignite them. That’s why they used to take a canary down into the mine. [If the canary keeled over in its cage, it signified explosive gases were in high concentration, and the miners knew that they’d better leave the area immediately.]

Any kind of lamp with a flame is pretty handy if you want to warm your hands. The carbide lamp’s flame sticks out from its side, and I’ve used it for thawing out padlocks.

Carbide lamp. (Image credit 54)

I’ve never had any problem getting carbide, though in some places it might be a challenge. I usually get it at a hardware store.

* * *

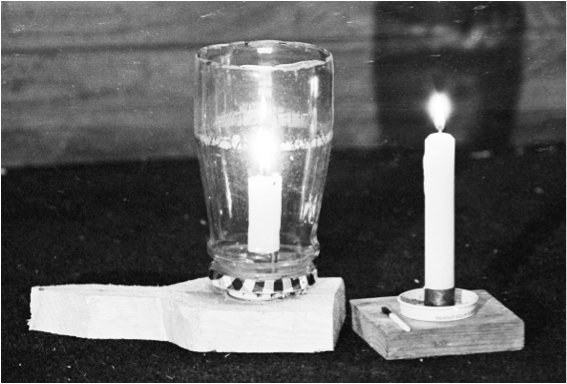

Oliver also used candles quite a bit. He made a candle holder by cutting the bottom off a bottle, flipping it, and then nailing the bottle’s lid to a board to create a portable lantern.

Oliver’s portable candle lantern. Image by Curt Madison

He cut the bottle by soaking a string in kerosene, wrapping the string around the bottle, and setting the string on fire to create a ring of heated glass. He’d then pour cold water over the bottle, and the uneven contraction of the hot and cold parts would cause the bottle to crack along that line.

To make a candle lantern for outdoor use, he’d cut a window in one side of a tin can and fasten the can to a board with the candle inside. When he walked with that window facing forward, the breeze created by his motion wouldn’t blow the candle out because there was no second opening through which the air could exit.

* * *

In my tight little houses, it took quite a bit of ventilation to burn a kerosene or gasoline lamp. I didn’t like to leave my lamp venting system open when I wasn’t keeping much of a fire, so eventually, once they were available, I got some solar panels and LED lights. With my panels, even in the wintertime, I can keep a small battery charged enough to keep a few LED lamps going.

I have four panels that sit side by side in a frame near the end of the house. In the wintertime, they are usually standing straight up because most of the light is coming from pretty close to the horizon. I angle them back more at other times of the year when the sun is higher in the sky.

The panels are 3 feet tall and 18 inches wide. A bear once had a high old time playing with one of them and didn’t leave a piece of unbroken glass bigger than a dollar. Even so, the panel still worked a little bit. I was amazed.

I have two large deep-cycle batteries, rated at well over a hundred amp hours, that I can keep charged all summer. As fall approaches I start needing lights more often, but there isn’t a lot of power coming off the solar panels, so I use two smaller batteries of about four amp hours.

Solar power is an odd situation. I don’t need the system much in the summertime, when the big batteries are fully charged. Then in the wintertime, I don’t get much power to speak of from those panels on a clear day. But on a cloudy day—not snowing or dark, just overcast—the clouds seem to dissipate the sunlight and direct it downward so I get enough to charge one of the small batteries. Between the two of my small batteries, I usually have enough juice to keep my little LED lights working.

I put the LEDs on extension cords, one fastened permanently at the head of my bed, one on the far end of the house by my workbench, and another one that moves, either hanging above the stove or beside the sewing machine or the rocking chair where I sit and read.