Oliver and the rest of the crew of Dragon Lady waited in Bari for a backhaul on an empty C-47 freight plane. They had not yet completed the required number of missions to finish their tour of duty, but the military reassigned them on account of their twenty-eight days in Yugoslavia.

After a couple of days they caught a flight to Casablanca. Then they continued on to bases in Newfoundland, New York City, and Salt Lake City, where they went their separate ways.

Meanwhile Ed and Pansy, Oliver’s parents, had moved to Nampa, Idaho, a town of about 12,000 some twenty miles west of Boise, after Ed had quit his sawmill job in Snoqualmie, Washington. Ed purchased a truck and established a trash-hauling route in Nampa, and also hauled and sold firewood from a sawmill in the nearby town of Emmett. They endured a very difficult and stressful April while Oliver was missing in action in April of 1944.

By around the first of June 1944 Oliver had been assigned to a base in Galveston, Texas. Initially he served as an instructor, most likely once again in radio operations, but soon the military sent him for a short course to learn how to operate the radio in a B-29. Meanwhile the defense plants continued to develop and turn out improved aircraft at a steady clip, and the B-32 soon superseded the B-29.

Oliver never flew a training flight in the B-29, but he did qualify for service aboard the B-32, a new low-altitude bomber that flew below radar. His time in Galveston was short, although he did find time to swim at the beach and get stung by a sting ray, an injury that was very painful and took “a long time” to heal.

While the war was stressful and difficult for everyone, the anxiety must have been enormous for a family with four sons of military age. Oliver had been called up first, in 1942. Keith had asthma and was exempt. The next brother, Phillip, enlisted in February, 1943, and was a co-pilot on B-17s flying out of England. He only made a few flights before the end of the war, and returned home safely.

Carol enlisted in March, 1944 at the age of 18, and was assigned to the 78th Infantry Division, 309th Infantry Regiment. The unit left for Europe in October and arrived in Germany in mid-December, just in time for the Battle of the Bulge—the last major Nazi offensive against the Allies in World War II.

The division breached the Siegfried Line1 near the Hürtgen Forest in late December and continued to fight their way into the heart of Germany, capturing the huge Schwammenauel Dam and then—famously— The Lundendorff railroad bridge at Remagen, allowing the Allies to cross the Rhine River, an unexpected advantage since the Germans were blowing up all the bridges across the Rhine. Books, and even a movie, have been written about this event, which was a great boost to the Allied effort to win the war. Thus, Oliver’s brother’s Division, the 78th, became the first infantry division to cross the Rhine—an achievement that signaled the final stage in the defeat of the Nazis. The Remagen Bridge was captured by the Americans on March 7, 1945. Carol was killed two days later, on March 9, when the Germans began a fierce but ultimately unsuccessful attempt to retake the bridge. He is buried in Belgium.2

By that time Oliver had been assigned to Mountain Home Air Force Base. Since the base was only sixty miles from Nampa, he was able to spend his weekends with his parents and his siblings Keith, Jessie and Dell. (Phillip was still in England.)

Keith introduced Oliver to his circle of friends, among them a young woman by the name of Lorene Flynn. She also had family in the area, and was studying elementary education at Northwest Nazarene College, a local private school.

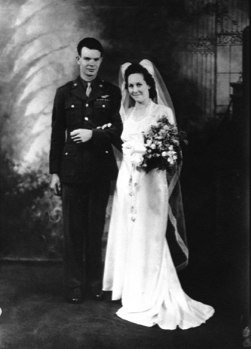

Like many of his fellow returning soldiers, Oliver married right away. He and Lorene—all his life he would call her Rene (pronounced “REE-Nee”)—married on June 14, 1945, while he was still in the service. They bought a small trailer house, parked it on a big farm off-base, and began their married life.

Photo from the Cameron family collection.

The B-32, for which Oliver had trained, flew its first combat mission a couple of weeks later. However, the atomic attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki led to Japan’s unconditional surrender on August 15, 1945, before Oliver could again see combat. The war was winding down. Oliver spent his final days in the service as a flight radio instructor.

The military began releasing soldiers on a point system that favored those who had served overseas the longest. In spite of the fact that Oliver’s overseas tour had been very intense, he had only been abroad for six months. As a result, he had to wait longer than some others.

Never one to sit still, he quickly found work. One of his first off-base jobs during this time was on the South Fork of the Boise River, about 20 miles northeast of Mountain Home, where the Anderson Ranch Dam was under construction. On his days off, Oliver would drive out to the site and help clear sagebrush and rocks.

He finally received his discharge on October 18, 1945. After collecting $250 in separation pay, Oliver was free—finally—to return to civilian life.

He and millions of other newly released soldiers then began the process of adjusting to peacetime. Horrific wartime experiences fueled their drive and passion to put the nightmares behind them and move forward with building homes, families, and careers. As Tom Brokaw noted in The Greatest Generation, this group of young men and women would become one of the most innovative and productive in American history.

The United States made efforts to honor and assist returning veterans. Many of them took advantage of The Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, commonly known as the GI Bill of Rights, to go to college—an opportunity undreamed of before the war. The government also offered GI Loans for business startups or home purchases.

Oliver, the independent self-starter who considered himself done with formal education when he graduated from high school, declined the educational benefits of the GI Bill. As a child of the Great Depression, he also avoided excessive debt. Even when it became the norm to borrow for a new house or car, he stayed true to his principles.

Although it was a great relief and a source of hope to get back to “real life” and to be among friends and family after the war, Oliver found that it was hard to find work in western Idaho. He and Rene moved from Mountain Home to Nampa, where he picked up whatever temporary jobs he could find, such as dismantling old railroad cars. While he had this job in the railroad yard, he and Rene lived in a rooming house on the north side of Nampa.

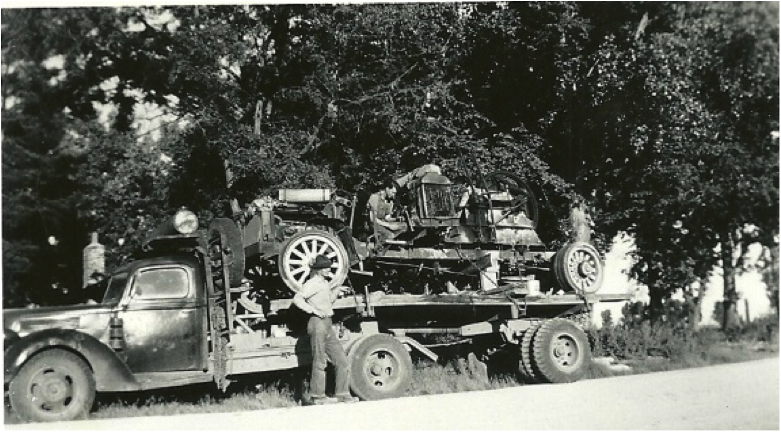

He did tap into his GI benefits in order to purchase a former military truck. He cut the chassis just ahead of the transfer case, lengthened the frame by 34 inches, and built wooden bunks—metal frames for holding a load—on the bed for hauling logs.

He started getting jobs, but not everything went as planned.

That’s when I got caught in the avalanche and come pretty near getting squashed.

It was spring; the snow on the ground was thawing, creating runoff and making the steep roads in the Idaho mountains nearly impassable. Oliver got a job hauling logs to a sawmill in the mountains outside of Idaho City. The trucks had to be pulled up high on the mountain to the loading site with a caterpillar tractor due to the poor condition of the switchback roads, and driven back down to the sawmill.

Oliver had just made new bunks and had cables attached to hold up the side stakes of the bunks. The first layer of logs—the deck load—needed to be tight, but the loader put in a log that didn’t fit, so they dropped another log onto it to force it in place, which broke the cable clamp loose from the bunk stake. To compensate for that, and to secure the load, Oliver ran a chain from the trailer hitch around the outside log, effectively tying the load to the truck, a big mistake.

As Oliver started to drive away to take his load down the mountain to the sawmill, the water- saturated road started to give way, and Oliver’s load slid off. This was a big enough calamity, but since Oliver had tied the truck to the corner log, the falling load of logs pulled the end of the truck around. The truck started rolling sideways. As the truck rolled down an embankment toward another road just below, the cab protector was smashed down, the cab door was thrown open and Oliver went flying. He landed hard on his neck and shoulder, doubling him up, and then proceeded to roll down the hill just behind the truck. The truck landed on its wheels on the lower road, Oliver came down beside it, lying in line with the front axle. Looking up, he realized the truck was teetering precariously, and the wheel was positioned to land right on his chest. He rolled over once more; the wheel came down right beside him.

The other men got Oliver off the mountain by way of an old army ambulance that had been converted to a grease truck. Because of the deep snow, they had to pull the old ambulance with a caterpillar tractor—presumably the same one they’d used to pull the trucks up the road in the first place. At the foot of the mountain they transferred him into a crew member’s new car for the ride to the hospital in Boise.

Medical personnel set Oliver’s dislocated shoulder, but the X-rays were taken with Oliver lying flat and they failed to show the serious damage to his spine. He returned home after a few days.

By that time Oliver and Rene had moved into a house that belonged to Rene’s grandmother, at 204 Juniper Street in Nampa—an address that would figure in Cameron family life for many years to come. A nurse friend who lived nearby became concerned because Oliver was exhausted and only wanted to sleep all the time.

He was also having trouble holding himself upright. He saw another doctor, who X-rayed him from the side and discovered damage to four vertebrae in Oliver’s back. The new doctor put him in a body cast, and told him his working days were over. He later replaced the cast with a brace on Oliver’s back, with straps to hold him up.

Meanwhile, friends had towed Oliver’s truck home for him. In spite of what the doctor had told him, he promptly tried to go back to work. Very soon he discovered that the brace was inadequate to hold him upright while driving, so he set about to remedy that.

He went into his shop and got a piece of rod, bending it down his left front side across his abdomen and up the other front side. He fitted this with a strap across the back to hold himself in place and discovered he could sit up and drive this way. He continued hauling logs for another two weeks.

He was, however, still under the doctor’s care. When he had an appointment, he planned his day to get back to Nampa early, change out of his telltale work clothes and put on the “official” brace. This continued until one day there was not enough time to change and he realized he was fed up with the subterfuge—“monkey business,” he called it.

He was sitting in the waiting room in his work clothes when the doctor came by and did a double-take. The doctor’s face got “kind of cloudy,” Oliver recalled, and when he was called into the examining room, the doctor kicked the door shut and began to berate Oliver for working and for not wearing his brace.

Oliver had a hard time keeping his face straight, but began unbuttoning his shirt to show the angry doctor his do-it-yourself brace. The doctor took more X-rays, reported Oliver was healing faster than expected, and that they should “get a patent on that thing.” Oliver wore his homemade brace for another nine months.

Oliver continued hauling logs for a time, mostly in the forested mountains north or east of their home base in Nampa.

Meanwhile, tragedy again struck Oliver’s family. His brother Keith suffered severe burns in an explosion while working in the basement of a Nampa hospital. He died of his injuries a few days later, on July 18, 1947. Oliver had lost his nearest brother and friend.

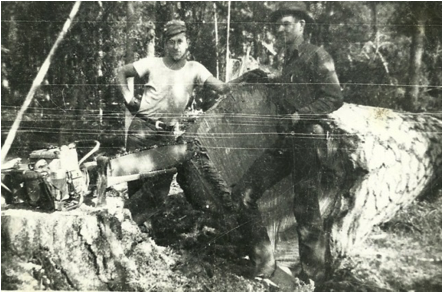

Photo from the Cameron Family Collection.

As they dealt with this devastating blow, Oliver and Rene continued to pursue their dream of a home and family. But as the peacetime economy swung into motion, GM and Ford began manufacturing trucks that were larger and hauled more logs on less gas than Oliver could with his converted military truck. That made it harder and harder for him to compete.

Rene gave birth to a son, Richard, on August 5, 1948 in Nampa. Six weeks later the little family moved to Smith’s Ferry, a tiny community in the mountains seventy miles north of Nampa. There Oliver found work hauling logs for the owner of a small sawmill.

Smith’s Ferry, Idaho.

Photo from the Cameron Family Collection.

Oliver and Rene prepared for the move by storing their belongings in a small rental unit on an alley, for which they paid $10 per month. On weekends they returned to Nampa to wash clothes and to retrieve stored food items.

In Smith’s Ferry they shared housing with the sawmill owner. When that living situation became too cramped, Oliver built an eight by twenty foot house on a trailer and moved it up into some trees across the tracks from the owner’s home.

In this peaceful, private location there was a small fenced play area for Richard, and Rene could wash clothes in a washing machine outside. Oliver rigged the washing machine’s electric pump to pressurize water that Rene had heated in a Jiffy electric heater, creating the luxury of a hot after-work shower for Oliver.3

Photo from the Cameron Family Collection

Photo from the Cameron Family Collection

Oliver and Rene were cozy in their little trailer in the woods, but steady long-term sawmill and logging work was scarce. Of course Oliver had other skills, but he was always wondering where his next job might turn up. In November of 1949, while he was helping a young friend and his wife move, a stranger asked if he knew a carpenter. Oliver replied he was a carpenter, and the man asked if he could come to work. Oliver told him he could start as soon as he finished moving his friend. The man handed him a big roll of blueprints. He had just been hired to oversee building a large shop for a road building company.

He had men working there that could have done the job, but they weren’t carpenters. We built a light plant [to provide electricity and light for a construction site] the first thing. It had 4 generators in it. The lumber was cold and would split if a nail was driven into it. We used the electricity to drill holes instead.

The shop was big. It had a frame on each side with a couple of railroad wheels on a rail on each side so that a beam could roll across. There was a big I-beam so that you could pick up the engine out of a [Caterpillar tractor] and move it or whatever you wanted to do.

Oliver and Rene were living in beautiful country, and their housing arrangements, while not plush, were adequate for their small family. Both had grown up living close to the land and eating homegrown vegetables, meat, and fruit supplemented with fish, berries, and edible wild plants. They bought a few items from the store and had fresh milk delivered by truck every other day from the larger town of Cascade. If Rene failed to show up for the milk delivery, the driver left it in a designated spot.

Oliver also hunted to supplement their diet. In his younger years he’d learned how to butcher and process deer, rabbit, pheasant, quail, and the occasional elk or bear.

In early 1950 Oliver and Rene welcomed daughter Dorene, but not without some suspense and drama. Near the end of the pregnancy Oliver’s mother had insisted that Rene stay with family in Nampa. Richard stayed with Oliver’s parents Pansy and Ed and siblings Jessie and Dell in the nearby town of Tamarack.

Oliver missed the first call warning him of Dorene’s impending arrival—he’d been out skiing. Dorene complicated things, though, and slowed the process down so Oliver still arrived in time. The baby lay in an awkward position, hand by head. This resulted in some tense moments. At one point, the doctor told Oliver he might not be able to save both mother and baby, and asked him to choose. Oliver, with one young child at home, of course chose his wife. Fortunately, the doctor was able to turn the baby and delivered her breach.

Photo from the Cameron Family Collection.

Photo from the Cameron Family Collection.

Oliver continued with his carpentry. When the crew finished building the shop, he stayed on as a “grease monkey,” working on heavy equipment. However, he was under pressure to join a union. Rather than join what he believed to be a corrupt organization, he quit.

Once more out of work, Oliver fell back on his logging skills, purchasing a chainsaw and getting work falling and bucking (cutting into lengths for hauling) timber near Warm Lake, Idaho.

Oliver and his family moved to a comfortable camp spot at Warm Lake in the mountains of northern Idaho that had a beautiful view and was surrounded by pine forests, resorts and ranches. They lived in a large tent that had lumber walls four feet up and a wooden floor covered with linoleum.

Since Oliver was fast and was paid by the number of board feet he cut, the money was good—while it lasted. He got one more job in that area cutting a patch of timber. When that job was finished, there was no more work. “That’s when I started thinking about going to Alaska.”

Circa 1951. Photo from the Cameron Family Collection.

In his accounts, Oliver mentions little about his religious upbringing, but his mother, Pansy, apparently took faith seriously. She had prayed for healing while she was sick with tuberculosis, and she believed that God had answered her prayers. That was a turning point in the family’s spiritual life. She’d become a regular churchgoer, and Ed had joined her.

Oliver was a spiritual man and still attended church with his family, but he found much to question in traditional Christianity as practiced around him. Nevertheless, his belief in God and in divine guidance played a huge role in the decisions he made—and in the resulting impacts on his family. With the war behind him, a scarcity of steady, well-paying jobs in Idaho, and a wife and family to support, he began seeking God’s direction:

I had been reading a religious book. He [the author] gave an itemized statement of how we could know what we were supposed to do as Christians. One of those things was if a subject came up that hadn’t been a special interest before and then every little bit it would come up again, we should pay special attention to it.

I read an article about Alaska and then just about every piece of paper I picked up, there was something about Alaska. Also, I wanted to get some property of my own, and that looked like a possibility of doing it, and so I decided to see if I could.

Under the Homestead Act of 1862, farmers who would live on the land, farm it, and build certain improvements could acquire title to 160 acres of land, or—with an act added in 1898—80 acres in Alaska. This is what seemed to offer a way into land ownership to Oliver, as it had to his forefathers.

Under the provisions of the Act, millions of Americans had settled large areas of the West and Midwest. By 1934, 1.6 million homesteads had been granted, some 270 million acres—about one-tenth of all federally-owned land in the United States.4

As he conducted his research in 1950, Oliver found that most of the usable land in the West and Midwest had already been claimed. However, land was still available in Alaska.

The United States had expressed interest in acquiring Alaska as early as the 1840’s, but had shelved the idea until after the Civil War.

The Russians had offered to sell the territory to the United States in 1859, hoping that its presence in the region would offset the plans of Russia’s greatest regional rival, Great Britain. However, the American Civil War was a more pressing concern in Washington, and no deal was reached.

Russia continued to see an opportunity to weaken British power by causing British Columbia to be surrounded or annexed by American territory. In early March, 1867, following the Union victory in the Civil War, the Tsar instructed the Russian minister to the United States to resume negotiations with Secretary of State William Seward.

After an all-night session, the negotiations concluded with the signing of a treaty on March 30, 1867. The purchase price was set at $7.2 million, or about two cents per acre. (In 2014 dollars, $119 million or eight cents an acre.)

Although the public had mixed feelings and referred to the agreement as “Seward’s Folly,” President Andrew Johnson agreed to the plan. Congress approved the treaty for the transfer by a wide margin and paid Russia, in gold. The transfer ceremony took place in Sitka in October, 1867.5

When asked what he considered to be his greatest achievement as Secretary of State, Seward replied “The purchase of Alaska—but it will take the people a generation to find it out.” 6

Later changes to the 1898 act extending the Homestead Act to Alaska Territory increased the amount of land that could be claimed from 80 to 160 acres, allowed claimants to file for five-acre homesites, and created a special program for returning veterans who wanted to farm in Alaska.7

Another incentive was the newly opened Alaska Highway. Built during World War II to aid the war effort, the road, mostly gravel, had a reputation as a rough and challenging drive. Still, it made a way for those with a sense of adventure and pioneer spirit to travel north.

The changes to the Homestead Act and the newly-opened land route gave Oliver incentives for moving to Alaska, and he decided to relocate. He and his young family were still living at Warm Lake, Idaho at the time.

However, Rene’s enthusiasm lagged behind his. She was enjoying their life in Idaho, and she loved being close to her mother, Oliver’s family, and her friends. She also had two small children to think about. Her parents even drove up from Nampa in a futile attempt to talk Oliver out of his scheme.

He remained adamant, and eventually the family reconciled themselves to the inevitable, dried their tears, and turned their attention to preparations for the trip. Oliver purchased a trailer and a Pontiac coupe with a gas-guzzling Buick engine that was heavy enough to pull it, and by August of 1951 they were ready to roll.

After one more round of tearful goodbyes, they headed for Edmonton, Alberta, the only route from Idaho to the beginning of the Alaska Highway. Oliver apparently took the highway in stride. After all, he had long experience in driving trucks on the narrow, winding roads of Idaho’s mountain country.

The beauty and variety of the scenery—farms, mountains, glaciers, rolling planes, and rivers—offset the length of the trip and the challenging conditions. Neither Oliver nor Rene, in their accounts, remarked much on the notorious roughness of the road.

The family camped in a tent at night, unless they had put in so many hours driving that they simply slept in the car. Every afternoon, preschoolers Richard and Dorene napped foot to foot in the back seat.

The Cameron family arrived in Fairbanks just after Labor Day, 1951.

1The original Siegfried Line was a line of defensive forts and tank defenses built by Germany in northern France during World War I. In English, “Siegfried line” more commonly refers to the similar World War II defense line that was built during the 1930s. It stretched more than 390 miles and consisted of more than 18,000 bunkers, tunnels and tank traps. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Siegfried_Line

2The 78th Division Veteran’s Association Lightning Division, “History of the 78th Lightning Division.” http://www.78thdivision.org/

3Details about daily life during Oliver and Rene’s early married years are taken from “More Than a Story,” a personal account by Rene Cameron.

4Potter, Lee Ann and Wynell Schamel. “The Homestead Act of 1862.” Social Education61, 6 (October 1997): 359-364. . http://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/homestead-act/

5Wikipedia: Alaska Purchase. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alaska_purchase

6Wikipedia: William H. Seward. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_H._Seward#Territorial_expansion

7Bureau of Land Management: Important Homestead Laws for Alaska http://www.blm.gov/ak/st/en/prog/cultural/ak_history/homesteading/AK_Homestead_Laws.html

8Wikipedia: Northwest Staging Route. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Northwest_Staging_Route

9Wikipedia: The Alaska Highway. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alaska_highway

Appendix

The Alaska Highway

As early as the 1930’s, the United States had considered a highway through British Columbia and Yukon Territory to link Alaska with the Lower 48 states. However, insufficient support in Congress had stalled the proposal. The Canadian government was also reluctant to undertake the effort and expense of a road that, in their view, would benefit only a few thousand residents of the northwestern part of the country.

Those attitudes changed on December 7, 1941 when the Imperial Japanese Navy carried out a surprise attack on the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. The strike dramatically revealed both the aggressive intentions of the Japanese and the extreme vulnerability of the West Coast of the United States. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt declared war on the Empire of Japan the next day, marking America’s entry into World War II.

American lines of communication with Alaska by sea were also seriously threatened, and alternative routes had to be opened. Canada and the United States, through the Permanent Joint Board on Defense, had decided in the autumn of 1940 that a string of airfields and radio ranging stations should be constructed or upgraded between the city of Edmonton in central Alberta and the Alaska-Yukon border, at Canadian expense. The Canadian government announced completion of the project late in 1941.8

It soon became clear that it was in the best interests of international defense to upgrade the primitive airfields, and to connect them with a service road that would also offer a means for transporting essential supplies to the Alaskan outposts. On February 7, 1942 President Roosevelt directed the Army Corps of Engineers to begin the construction of the Alaska Highway from Dawson Creek, British Columbia to Delta Junction, Alaska—a distance of 1,500 miles—and to complete it before the next winter.

Canada agreed to allow construction, with the understanding that the United States would bear the full cost and would turn the road and other facilities within its territory over to Canadian authority after the end of the war.

Through much of early 1942 the Japanese won battle after battle and took one South Pacific island after another. On February 23 a Japanese submarine shelled an oil refinery in Santa Barbara, California. Concerns about an attack and invasion along the West Coast skyrocketed.

Then, on June 3-4, 1942 Japanese forces attacked the Dutch Harbor Naval Operating Base and nearby Fort Mears in the eastern Aleutian Islands, with some loss of American lives. Two days later they invaded and occupied the islands of Attu and Kiska at the other end of the island chain.

Image: http://www.jimmymack.org/images/maps/aleutians_map.gif

The outermost island of Alaska’s Aleutian Islands lay only a few hundred miles from Japanese soil, and an invasion via the island chain would have met little resistance. Alaska had a small population and only a few thousand troops with a few planes on scattered bases—a totally inadequate force for such a huge landmass.

The Army threw thousands of engineers and enlisted men into the Alaska Highway project, mostly young men with little experience in heavy-equipment operation, road building, and arctic conditions. They faced rugged terrain, heavily forested mountains, boggy muskeg, melting permafrost, isolation, and hordes of hungry mosquitoes.

Nevertheless, to their great credit, they completed the job by the end of October, 1942, and the highway was dedicated on November 20, 1942. The successful completion of the road gave a much-needed boost to the morale of the American public.

By that time the tide of the war in the Pacific had begun to turn, easing some of the pressure regarding the defense of the West Coast. The military used the road in conjunction with the Northwest Staging Route, a series of airports built to ferry planes to Russia to aid in the war effort.

1944 at Ladd Field,

Fairbanks Alaska prior to its flight to the Russian front as a Lend-Lease aircraft.

The United States turned the Canadian portion of the Alaska Highway over to the Canadian government on April 1, 1946, and the road opened for general public use in 1948.9